November/December 2006

Adventure Travel

By Karen Kefauver

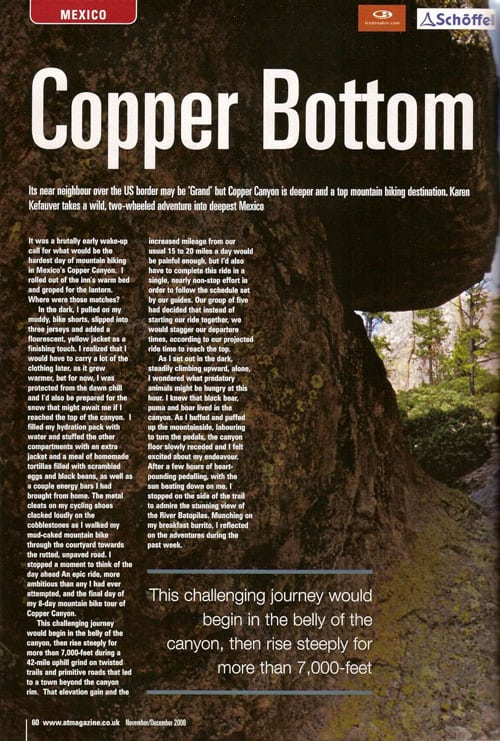

Its near neighbor over the US border may be ‘Grand’ but Copper

Canyon is deeper and a top mountain biking destination. Karen Kefauver

takes a wild, two-wheeled adventure into deepest Mexico.

It was a brutally early wake-up call for what would be the hardest day of mountain biking in Mexico’s Copper Canyon. I rolled out of the inn’s warm bed and groped for the lantern. Where were those matches?

In the dark, I pulled on my muddy, bike shorts, slipped into three jerseys and added a flourescent, yellow jacket as a finishing touch. I realized that I would have to carry a lot of the clothing later, as it grew warmer, but for now, I was protected from the dawn chill and I’d also he prepared for the snow that might await me if I reached the top of the canyon. I filled my hydration pack with water and stuffed the other compartments with an extra jacket and a meal of homemade tortillas filled with scrambled eggs and black beans, as well as a couple energy bars I had brought from home. The metal cleats on my cycling shoes clacked loudly on the cobblestones as I walked my mud-caked mountain bike through the courtyard towards the rutted, unpaved road. I stopped a moment to think of the day ahead An epic ride, more ambitious than any I had ever attempted, and the final day of my 8-day mountain bike tour of Copper Canyon.

This challenging journey would begin in the belly of the canyon, then rise steeply for more than 7,000-feet during a 42-mile uphill grind on twisted trails and primitive roads that led to a town beyond the canyon rim. That elevation gain and the increased mileage from our usual 15 to 20 miles a day would be painful enough, but I’d also have to complete this ride in a single, nearly non-stop effort in order to follow the schedule set by our guides. Our group of five had decided that instead of starting our ride together, we would stagger our departure times, according to our projected ride time to reach the top.

As I set out in the dark, steadily climbing upward, alone, I wondered what predatory animals might be hungry at this hour. I knew that black bear, puma and boar lived in the canyon. As I huffed and puffed up the mountainside, labouring to turn the pedals, the canyon floor slowly receded and I felt excited about my endeavour. After a few hours of heart-pounding pedalling, with the sun beating down on me, I stopped on the side of the trail to admire the stunning view of the River Batopilas. Munching on my breakfast burrito, I reflected on the adventures during the past week.

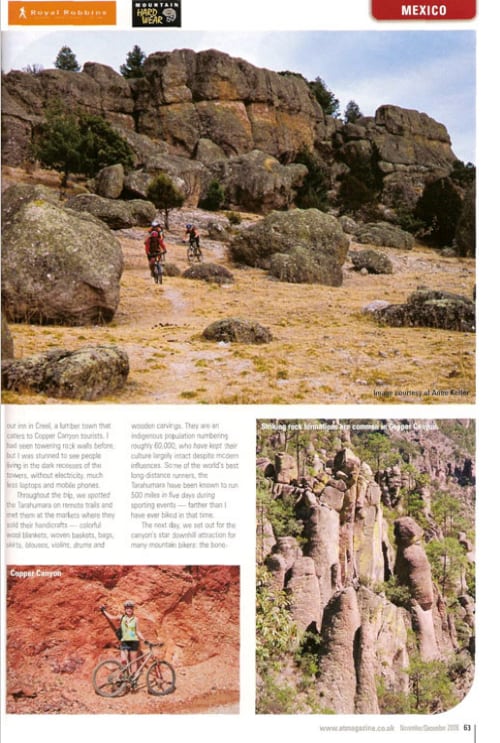

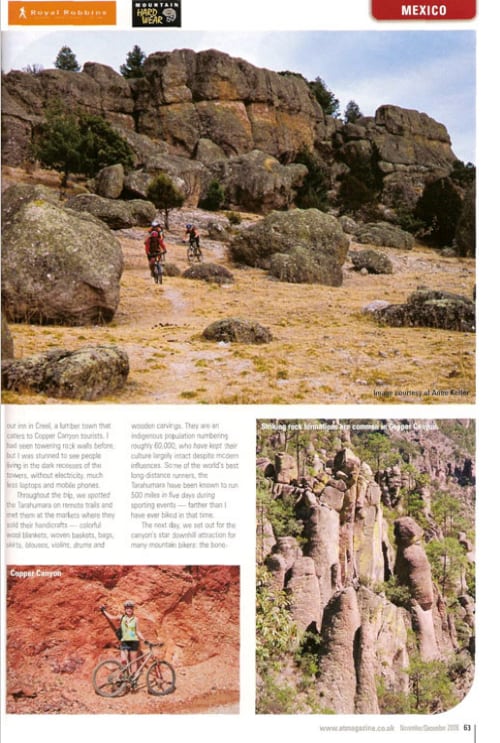

‘This trip is not for wimps,’ our guide, Andy, had warned us on the first day of hiking in Copper Canyon. ‘This is very challenging terrain’ he said. ‘On one of our expeditions here, we had 18 flat tires in a day.’

I figured that since it was mid-February, and we’d traveled to El Paso, Texas, from all across the U.S. to join this knobbly-wheeled expedition, that we were a determined bunch. Our guides, Andy and Noe, from Arizona, were both expert mountain bikers and fluent in Spanish. They would help us avoid major catastrophes like falling off the cliff side and careening into stray animals. While one guide drove our support vehicle, the other directed us on serpentine singletrack trails and twisted, rocky roads. They swapped tasks daily. Given the lack of decent roads and the scarcity of detailed maps, I appreciated how well they knew the vast Copper Canyon.

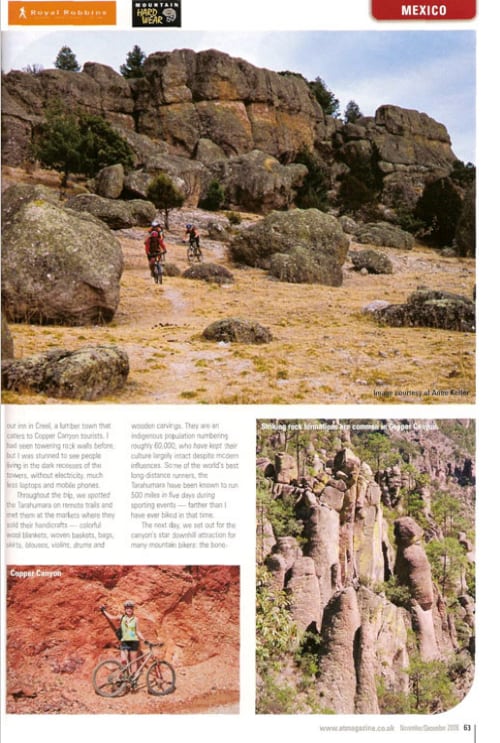

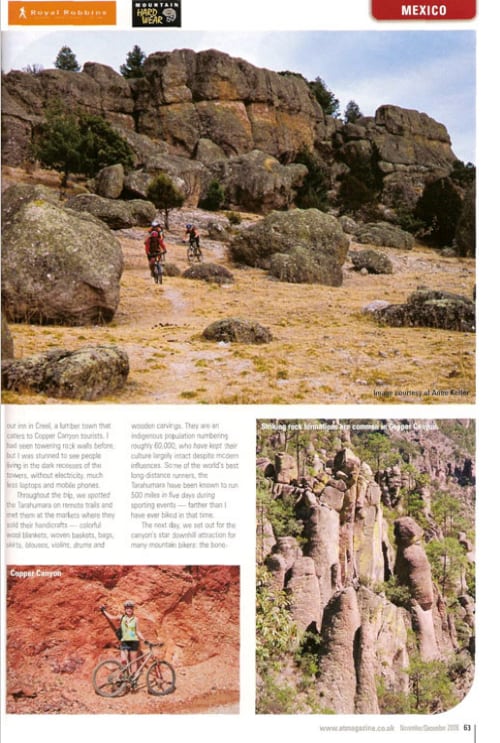

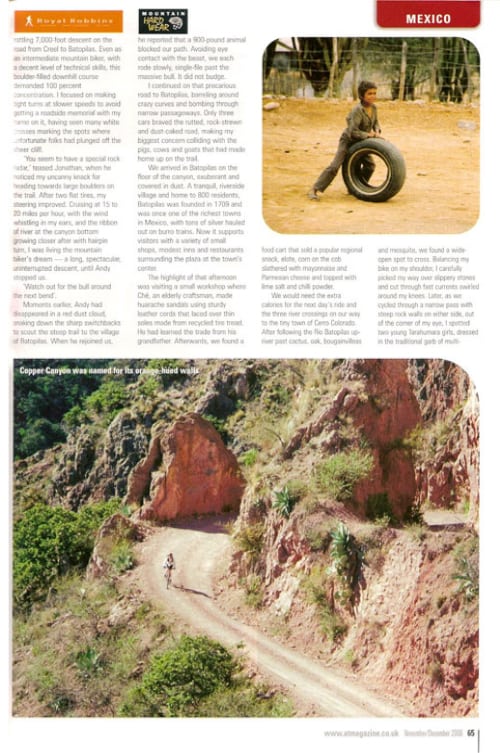

Located in the northern Mexican state of Chihuahua, Copper Canyon, or Barranca del Cobre, is one of six huge, interlocking chasms that traverse the Sierra Madre Occidental, covering an area four times the size of the U.S. Grand Canyon. The canyon encompasses a variety of microclimates ranging from the alpine forests standing at the canyon rim, through cactus and flower meadows blooming midway down to the tropical brush thriving at the bottom. The name Copper Canyon was inspired by the area’s mining industry as well as the rich rusty color of the cliff faces.

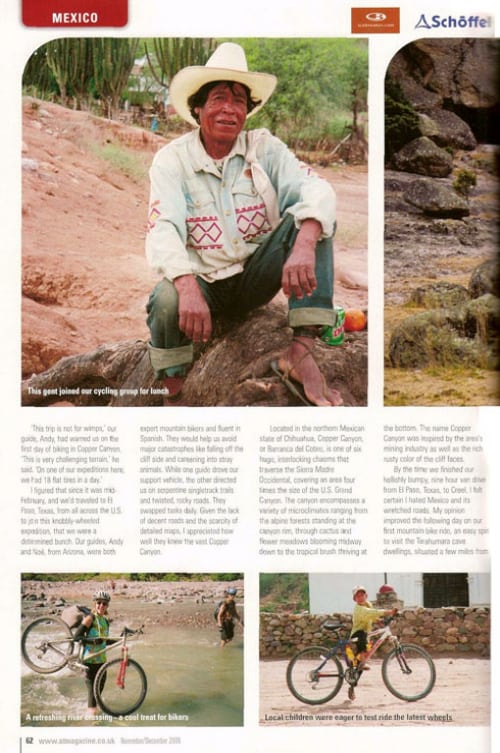

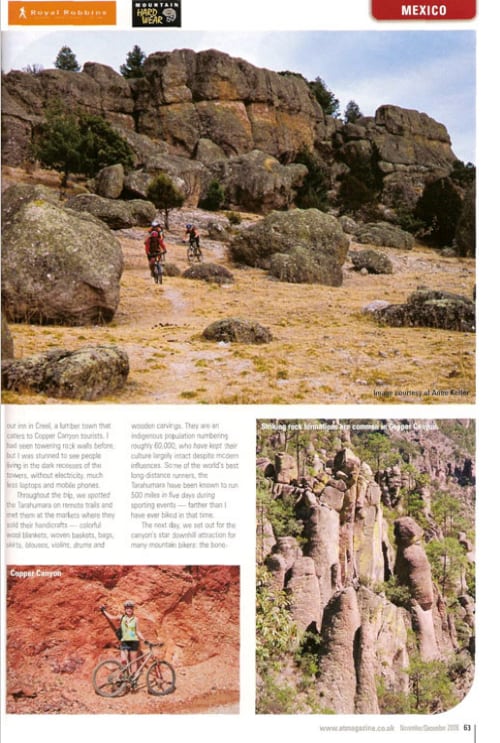

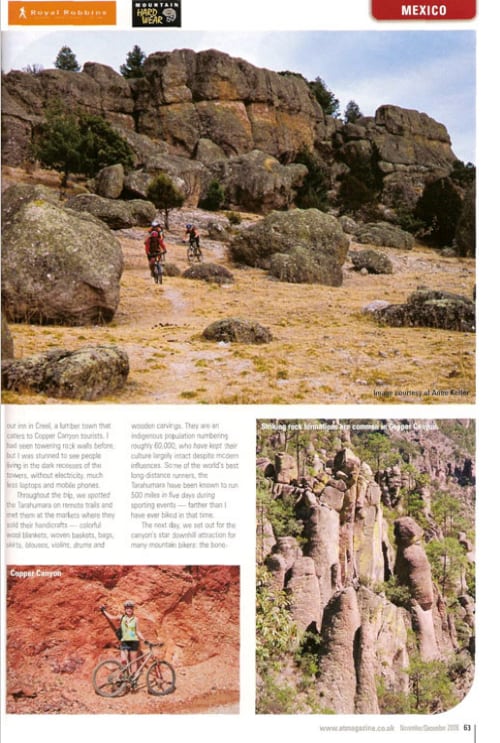

By the time we finished our hellishly bumpy, nine hour van drive from El Paso, Texas, to Creel, I felt certain I hated Mexico and its wretched roads. My opinion improved the following day on our first mountain bike ride, an easy spin to visit the Tarahumara cave dwellings, situated a few miles from our inn in Creel, a lumber town that caters to Copper Canyon tourists. I had seen towering rock walls before, but I was stunned to see people living in the dark recesses of the towers, without electricity, much less laptops and mobile phones.

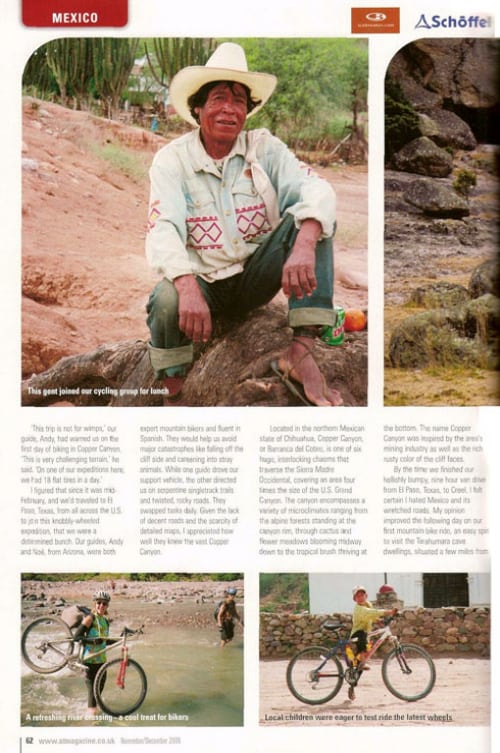

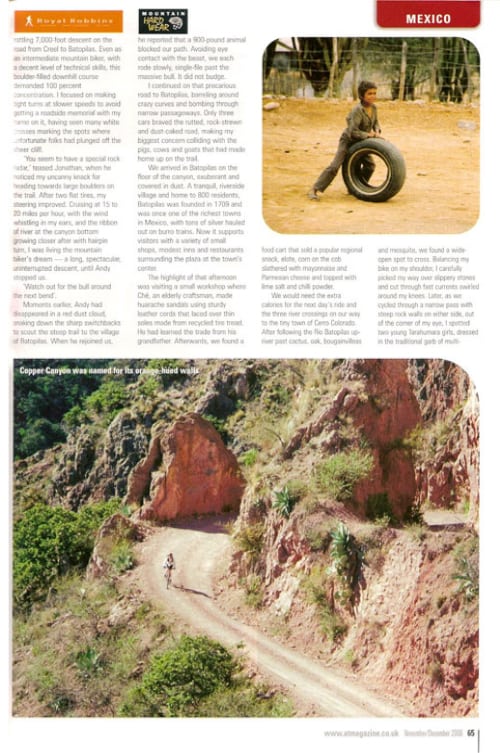

Throughout the trip, we spotted the Tarahumara on remote trails and met them at the markets where they sold their handicrafts — colorful wool blankets, woven baskets, bags, skirts, blouses, violins, drums and wooden carvings. They are an indigenous population numbering roughly 60,000, who have kept their culture largely intact despite modern influences. Some of the world’s best long-distance runners, the Tarahumara have been known to run 500 miles in five days during sporting events — farther than I have ever biked in that time.

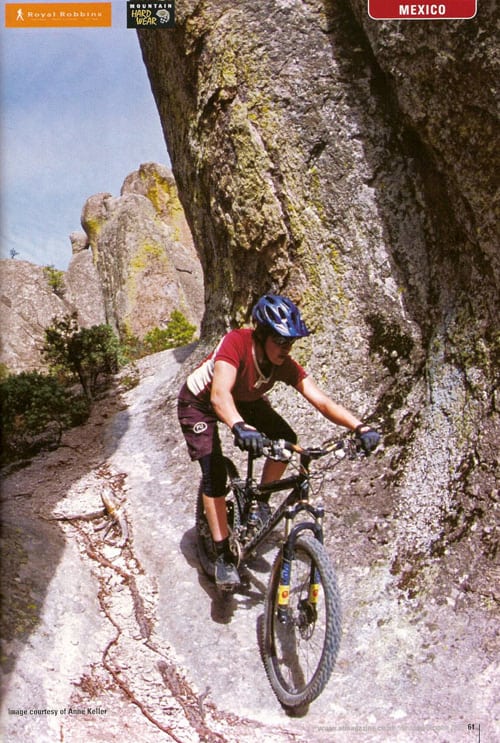

The next day, we set out for the canyon’s star downhill attraction for many mountain bikers: the bone-rattling 7,000-foot descent on the road from Creel to Batopilas. Even as an intermediate mountain biker, with a decent level of technical skills, this boulder-filled downhill course demanded 100 percent concentration. I focused on making rght turns at slower speeds to avoid getting a roadside memorial with my name on it, having seen many white crosses marking the spots where unfortunate folks had plunged off the sheer cliff.

‘You seem to have a special rock radar,’ teased Jonathan, when he noticed my uncanny knack for heading towards large boulders on the trail. After two flat tires, my steering improved. Cruising at 15 to 20 miles per hour, with the wind whistling in my ears, and the ribbon of river at the canyon bottom growing closer after with hairpin turn, I was living the mountain biker’s dream — a long, spectacular, uninterrupted descent, until Andy stopped us.

‘Watch out for the bull around the next bend’.

Moments earlier, Andy had disappeared in a red dust cloud, snaking down the sharp switchbacks to scout the steep trail to the village of Batopilas. When he rejoined us, he reported that a 900-pound animal blocked our path. Avoiding eye contact with the beast, we each rode slowly, single-file past the massive bull. It did not budge.

I continued on that precarious road to Batopilas, barreling around crazy curves and bombing through narrow passageways. Only three cars braved the rutted, rock-strewn and dust-caked road, making my biggest concern colliding with the pigs, cows and goats that had made home up on the trail.

We arrived in Batopilas on the floor of the canyon, exuberant and covered in dust. A tranquil, riverside village and home to 800 residents, Batopilas was founded in 1709 and was once one of the richest towns in Mexico, with tons of silver hauled out on burro trains. Now it supports visitors with a variety of small shops, modest inns and restaurants surrounding the plaza at the town’s center.

The highlight of that afternoon was visiting a small workshop where Che, an elderly craftsman, made huarache sandals using sturdy leather cords that laced over thin soles made from recycled tire tread. He had learned the trade from his grandfather. Afterwards, we found a food cart that sold a popular regional snack, elote, corn on the cob slathered with mayonnaise and Parmesan cheese and topped with lime salt and chilli powder.

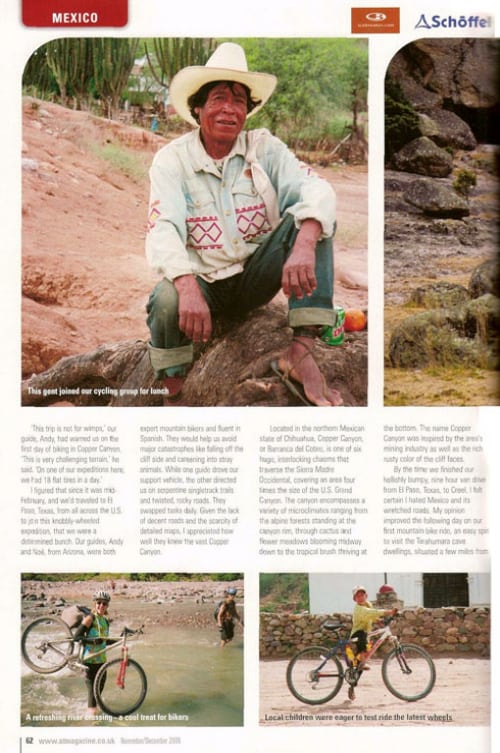

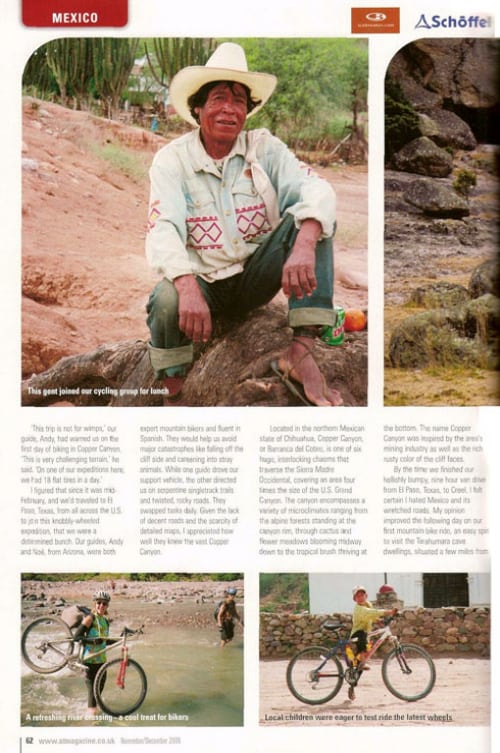

We would need the extra calories for the next day’s ride and the three river crossings on our way to the tiny town of Cerro Colorado. After following the Rio Batopilas up-river past cactus, oak, bougainvilleas and mesquite, we found a wide-open spot to cross. Balancing my bike on my shoulder, I carefully picked my way over slippery stones and cut through fast currents swirled around my knees. Later, as we cycled through a narrow pass with steep rock walls on either side, out of the corner of my eye, I spotted two young Tarahumara girls, dressed in the traditional garb of multi-colored woven dresses. We were easy targets for the girls, who scrambled down the steep wall of boulders to playfully ask us for candy and pens.

For our last daytrip from Batopilas, we rode our bikes to Mission Satevo, which was built on the canyon floor nearly 400 years ago by the Jesuits. At the mission we ate our picnic lunch and let the local kids ride our bikes. Dark storm clouds quickly gathered overhead. The skies unleashed a torrential downpour just as we finished our five-mile ride from the mission back to our lodging. The pounding rains raged through the night, but stopped in time for our epic climb up the canyon on our last day of the trip.

After polishing off my tasty tortilla lunch, I resumed my climb up the canyon. I pushed towards the top, but I could feel my energy slowly draining with the massive effort of ascending the bumpy, windy road. Even wearing all my layers of clothing, I was chilled to the point where I pulled out my extra tire tube and wrapped it around my neck like a rubber scarf. Fashion nightmare! At the rim I waited for the van to scoop me up for the long drive back to Texas and discovered that out of the five of us, only one managed to bike all the way to the top.

Who’s Writing?

Karen Kefauver lives in Santa Cruz, California, with her five bicycles and boyfriend. The pair enjoy taking cycling holidays and have mountain biked the rugged singletrack trails in Colorado and road toured in the canyon lands of Utah. They hope to explore Chile and Peru by two wheels in the near future.

Let’s Go…

Why?

Mountain biking in northern Mexico’s Copper Canyon is a one-of-a-kind trip because it blends daredevil downhill riding into the canyon and exciting cultural encounters with the Tarahumara Indians. The primary bike route from Creel to Batopilas is a bumpy, rock-strewn road. There are also plenty of technical singletrack trails in the rugged backcountry and slippery river crossings to navigate, but the trip is about more than just the biking.

When to go

Most organized mountain bike trips take place in October, November, January, February and March to avoid the intense spring and summer heat. It’s best to skip the rainy season from July to August. Weather and temperature conditions vary since the canyon area ranges in elevation from 1640-feet in Batopilas to 7875-feetin Creel. It can be 10-15 degrees [centigrade) warmer on the canyon floor than on the rim.

Getting there

Located in Mexico’s largest state of Chihuahua, Copper Canyon (also called Barranca del Cobre) is a rugged wilderness area in the sprawling Sierra Madre Occidental mountain range. The starting points for a Copper Canyon trip vary depending upon the tour company, but most flights from Europe ultimately end at one of two airports: in El Paso, Texas, near the U.S.-Mexico border, or at General Roberto Fierro Villalobos International Airport, also known as Chihuahua International. Most tour operators provide van transportation to the town of Creel, which is also accessible by both train and bus from points north. Creel is the most popular starting point for accessing Copper Canyon. While Creel’s main drag is packed with hotels, restaurants and gift shops, it still feels like a backcountry outpost.

Guides

Some backpackers don’t hire a guide and descend into the canyon on their own, but who knows if they make it back? Copper Canyon is part of a maze of 200 interlocking gorges that combine to form five massive interconnected canyons in the Sierra Madre Mountains. Plenty of space to get lost. Even fewer mountain bikers go unescorted because routes are not clearly marked and some singletrack trails are nearly impossible to find without help. If you have not signed up on an organized tour, ask around Creel to find a reputable, bilingual guide.

Mountain Bike Tours

Even deeper than Arizona’s Grand Canyon in some spots, Copper Canyon was not even fully documented until 1986. The best way to take advantage of the area is in a guided group tour on mountain bike. Tours generally follow the same route, starting near Creel and then riding from the top of the canyon, to the bottom, with visits to Batopilas and Satevo. Check with each operator about the skill levels of the riders since some trips are better adapted to the needs of more advanced cyclists. For mountain bike trips in Copper Canyon, here are some well established companies:

Equipment

You don’t need to buy a new bike for the trip, but having front or full suspension will make you a more pleasant person during the ride. Do pack a few extra tire tubes to carry with you since flat tires are a frequent occurrence thanks to all the jagged rocks. My hardtail Airborne mountain bike with its titanium frame held up fine on this trip.

Food & Drink

Dining in Mexico was a very satisfying part of the adventure. For dinners, we feasted on homemade meals, often served in restaurants that were rooms set up in peoples’ homes. The fresh, hot corn tortillas, salsa and corn were presented with chicken or beef. I also came to enjoy the flavor of cactus flesh, called nopales. We were told to use bottled water for drinking and brushing our teeth. I followed this recommendation and had no health problems. The restaurants selected by our guides offered bottled water on the menus and in more remote markets, we drank juice instead of water.

Useful websites, maps and books

For general travel information in Copper Canyon, including train travel schedule and fares, visit http://www.coppercanyon-mexico.com. To learn more about the Tarahumara, visit www.tarahumara.com.mx. The site www.visitmexicopress.com is a helpful overview on the state of Chihuahua. My favorite guidebooks with sections on Copper Canyon are Lonely Planet’s Mexico and Let’s Go Mexico. Good maps of the area are hard to come by outside of Mexico. Try searching the web and talking to the outfitters to locate current maps.

What to take

High SPF sunscreen in a stick form is especially handy to put in a bicycle jersey pocket. Headlamp. While some of our lodgings had electricity, once we were in the canyon, oil lanterns were the norm, so a headlamp was useful for reading at night. Camera. If you want to document your trip in photos, best play it safe and bring an old-fashioned film camera just in addition to a digital camera. For the digital, bring extra batteries and an extra memory card.

One full set of cycling clothes -socks, jersey, and shorts – per day. Don’t make my mistake and think you will feel like hand-washing your dirty clothes at the end of a hard day’s ride. Padded shorts are the best bet. Hydration Pack. This is a crucial piece of equipment to help keep you cool and hydrated. The additional space in the pack is useful to stash clothes, food and camera.

Notepad and pen. This is a great tool for keeping track of your adventures in a journal or for drawing pictures to communicate with locals.

Mini Spanish dictionary. Knowing some basic Spanish phrases is a great way to connect with the people you encounter, many of whom speak no or little English. A travel-sized phrasebook is helpful to carry around town after the rides.

Pencils, pens and candy for the kids. It’s fun to be a bicycling ambassador and share something with the kids in town who will playfully chase you on your bike.

Contacts

KE Adventurewww.keadventure.com

01768 7739S6

Western Spirit (US Based)

www.westernspirit.com

800-845-2453

Nichols Expeditions (US Based)

www.nicholsexpeditions.com

800-648-8488.

REI Adventures

www.REIadventures.com

800-622-223