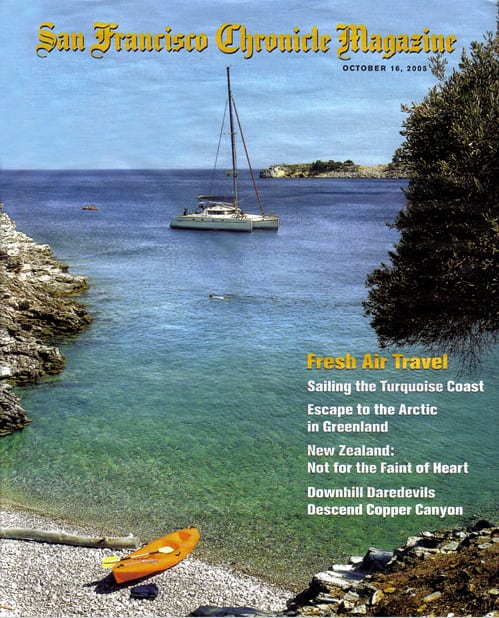

Downhill Daredevils Descend Copper Canyon

October 2005

San Francisco Chronicle Magazine

By Karen Kefauver

Watch out for the bull around the next bend,” warned Andy. Our guide had moments earlier disappeared in a red dust cloud, snaking down the treacherous switchbacks on his mountain bike to scout the steep trail to the village of Batopilas. Now he rejoined the group with the disturbing news that a 900-pound bull stood between us and our evening’s lodging. I glanced at my four fellow cyclists to see how they were taking the news. Having survived half of our eight-day mountain bike expedition in Copper Canyon, Mexico, it would seem a shame to perish now.

“Andalé!” commanded Andy in Spanish, urging us to get moving. I began a cautious descent toward the surly beast, dodging rocks and avoiding cactus lining the narrow, bumpy road—clutching the hand-brakes on my bike the entire way.

In the lead were the other participants in this adventure with World Trek Expeditions: Tom Caughlan, 52, a doctor from Kalispell, Mont.; Jonathan Fine, 33, an occupational therapist from Boston; Trevor Shepherd, 46, a computer engineer from Plano, Texas; and Rose Marie Hagy, 56, a manufacturing executive from Reading, Penn.

I held my breath while we squeezed single-file past the enormous black and white bull. The animal stared at us with its beady eyes, but made no move. “That was close,” said Rose, with a sigh of relief.

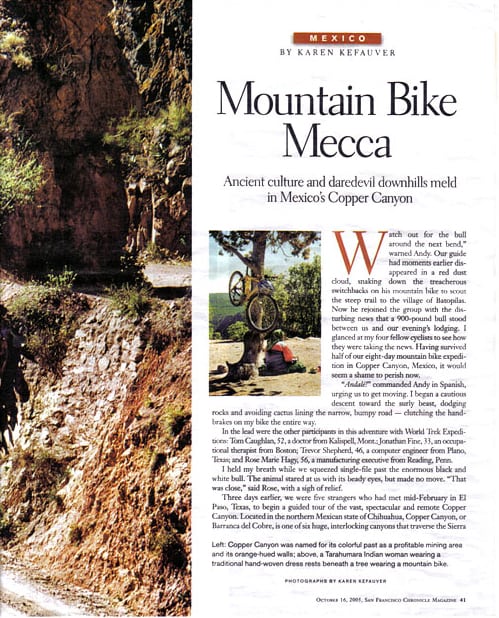

Three days earlier, we were five strangers who had met mid-February in El Paso, Texas, to begin a guided tour of the vast, spectacular and remote Copper Canyon. Located in the northern Mexican state of Chihuahua, Copper Canyon, or Barranca del Cobre, is one of six huge, interlocking canyons that traverse the Sierra Madre Occidental, covering an area four times the size of the Grand Canyon. In some spots, it’s 1,000 feet deeper than Arizona’s prized national park. The name Copper Canyon was inspired by the area’s 18th and 19th century mining industry, as well as the rich coppery color of the canyon walls. We dropped from alpine forests at the canyon rim, through cactus and flower meadows blooming midway, to tropical brush thriving at the bottom.

Over eight days, our Arizona-based guides, Andy Small and Noé Gámez, both expert mountain bikers who are fluent in Spanish, showed us the natural wonders of Copper Canyon — stunning panoramas of gaping orange-hued canyons, hidden hot springs, craggy rock towers and rain-swollen rivers. While one guide drove the support vehicle, a mini school bus outfitted with bike racks on the roof, the other directed us on serpentine singletrack trails and twisted, rocky roads.

“This trip is not for wimps,” said Andy, 36, in his typically blunt style. Without a knowledgeable guide, it would have been daunting to unravel the maze of the Canyon, given the lack of decent roads, the scarcity of detailed maps and the tangled administrative infrastructure. “This is very challenging terrain,” he said, recalling that on one of his five previous group expeditions, “we had 18 flat tires in a day.”

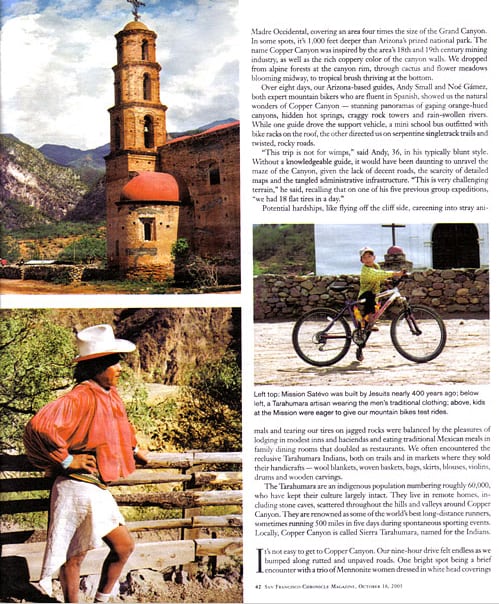

Potential hardships, like flying off the cliff side, careening into stray animals and tearing our tires on jagged rocks were balanced by the pleasures of lodging in modest inns and haciendas and eating traditional Mexican meals in family dining rooms that doubled as restaurants. We often encountered the reclusive Tarahumara Indians, both on trails and in markets where they sold their handicrafts — wool blankets, woven baskets, bags, skirts, blouses, violins, drums and wooden carvings.

The Tarahumara are an indigenous population numbering roughly 60,000, who have kept their culture largely intact. They live in remote homes, including stone caves, scattered throughout the hills and valleys around Copper Canyon. They are renowned as some of the world’s best long-distance runners, sometimes running 500 miles in five days during spontaneous sporting events. Locally, Copper Canyon is called Sierra Tarahumara, named for the Indians. It’s not easy to get to Copper Canyon. Our nine-hour drive felt endless as we bumped along rutted and unpaved roads. One bright spot being a brief encounter with a trio of Mennonite women dressed in white head coverings and loose, ankle-length dresses. In the early 1920s, a large group of Mennonites began to settle in Cuauhtemoc, near the state capital, Chihuahua City. Religious persecution over the centuries had pushed the Protestant sect from Holland to Poland to Russia’s Ukraine. They crossed the sea to Canada and eventually continued south to Mexico. Descendants of German-speaking colonists, many Mennonites became successful farmers and cheese-factory owners. We exchanged greetings in Spanish with the women while we waited in line to buy strawberry and lime frozen fruit bars at a roadside stand.

We launched the cycling portion of our trip from Creel, a lumber industry town known as “the Gateway to Copper Canyon” because it’s a bustling hub of hotels and restaurants geared toward backpackers and train travelers. The Chihuahua al Pacifico Railroad train, the region’s premier tourist attraction, carves through the mountains, winds through tunnels and provides breath-taking views on its 400-plus miles of track. The most popular and scenic route spans east to west, from Los Mochis, near the Pacific Coast, to the inland city of Chihauhua.

Preferring our mountain bikes to first-class train tickets, we stretched our legs on our first cycling excursion, a visit to the Tarahumara cave dwellings, which were a few miles from Creel. From the road, I studied the homes, doorless dwellings recessed into the slab of a massive rock wall, imagining what life would be like living inside a rock tower.

The next day, we set out for the canyon’s star downhill attraction for many mountain bikers: the bone-rattling 7,000-foot descent on the road from Creel to Batopilas. Even as an intermediate mountain biker, this boulder-filled downhill course demanded my full concentration. “You seem to have a special rock radar,” observed my fellow cyclist, Jonathan, noting my unfortunate tendency to steer toward the largest rocks in our path. Cruising at 15 to 20 miles per hour, with the wind whistling in my ears, and the ribbon of river at the canyon bottom growing closer after every hairpin turn, I was living the mountain biker’s dream — a long, spectacular, uninterrupted descent.

On that precarious road to Batopilas, I yielded to only three cars. Few drivers were willing to brave the rutted, rock-strewn and dust-caked road. Stray wildlife presented a far bigger danger than traffic collisions: I dodged three pigs, two cows, two goats, a horse and a rooster in one afternoon. The canyon is also home to black bear, puma, deer, boar and 300 species of birds, but I had no time to seek them out as I barreled around hazardous curves and pedaled through narrow passageways. I did stop to examine a white wooden cross planted beside the road — one of many memorials marking the spots where unlucky travelers had plunged off the sheer cliff.

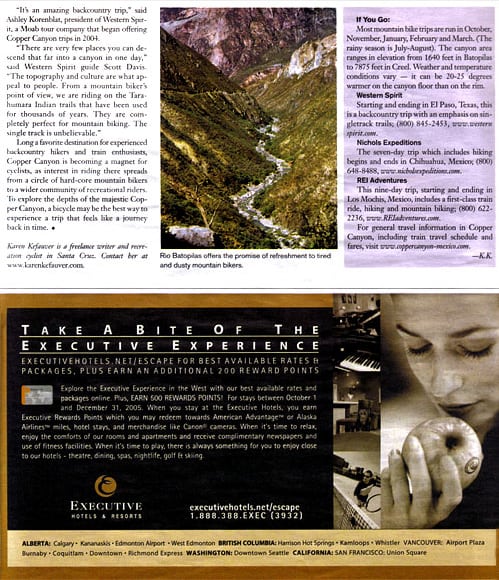

We arrived in Batopilas exuberant and covered in dust. Founded in 1709 and once one of the richest towns in Mexico, with tons of silver hauled out on burro trains, Batopilas today is a tranquil, riverside village with 800 residents. After a hard-earned hot shower at our inn, we set out to explore the small shops surrounding the plaza, the town’s center.

In a small workshop next to the plaza, an elderly craftsman named Ché, who had learned his trade from his grandfather, assembled huarache sandals using sturdy leather cords that laced over thin soles made from recycled tire tread. I tried on a pair and marveled at how the locals walked miles wearing the unpadded shoes. We stopped at a cart to buy elote, corn on the cob slathered with mayonnaise and Parmesan cheese and topped with lime salt and chile powder. We munched on this regional treat while standing on the wobbly foot-bridge that dangled above the roaring Batopilas River.

We faced three river crossings in our excursion the next day to the small town of Cerro Colorado. After following the Rio Batopilas up-river past cactus, oak, bougainvilleas and mesquite, we found a wide-open spot to cross. Balancing my bike on my shoulder, I carefully picked my way over slippery stones and cut through quick currents that swirled up to my knees. Later, I spotted two Tarahumara girls, dressed in traditional garb of multi-colored woven dresses. They had appeared seemingly out of nowhere, but then I realized that the 6-year-olds had scrambled down a steep wall of boulders from the cliffs above to ask us for dulces and plumas — candy and pens.

For our last daytrip from Batopilas, we rode our bikes to Mission Satevó, which was built on the canyon floor nearly 400 years ago by the Jesuits. Known as the “Lost Mission” because few records exist to describe its existence, it is one of the canyon’s best-preserved missions. As the only mountain bikers in town, we were quite popular with a band of local kids, whom we let test ride our bikes. Storm clouds were gathering, so we quickly set off on our 5-mile return trip to Batopilas. We got stuck in a traffic jam, trailing a yellow earth-mover that crawled toward town. It was impossible for us to pass without risking becoming another cross on the roadside. We barely made it back before the skies unleashed a downpour that lasted through the night.

The rooster’s crow at 5 a.m. alerted me that it was time to start our final day of cycling, an epic ride of 42-miles from the belly of the canyon to a town beyond its rim, with more than 7,000-feet of elevation gain — quite a dramatic change from our usual mileage of 15 to 20 miles a day. I set out before dawn, equipped with a heavy backpack stuffed with a plastic water bladder, extra clothing and leftover breakfast, a few homemade tortillas filled with scrambled eggs and black beans. The canyon floor slowly receded as I huffed and puffed up the mountainside, pushing my aerobic endurance to the limit. Only after I had reached the chilly forest on top, where I spotted patches of snow, did I succumb to exhaustion. I stopped and waited for the support vehicle to scoop me up for the long drive toward El Paso. It was the most satisfying climb I had ever experienced on a bike.

Our Copper Canyon bike trip in 2003 turned out to be World Trek Expedition’s last tour because the company president died unexpectedly a month later at age 33 during a trip to Thailand. Fortunately, a number of other companies, including Western Spirit, REI Adventures and Nichols Expeditions, conduct mountain bike trips to Copper Canyon.

“It’s an amazing back country trip,” said Ashley Korenblat, president of Western Spirit, a Moab tour company that began offering Copper Canyon trips in 2004.

“There are very few places you can descend that far into a canyon in one day,” said Western Spirit guide Scott Davis. “The topography and culture are what appeal to people. From a mountain biker’s point of view, we are riding on the Tarahumara Indian trails that have been used for thousands of years. They are completely perfect for mountain biking. The single track is unbelievable.”

Long a favorite destination for experienced back country hikers and train enthusiasts, Copper Canyon is becoming a magnet for cyclists, as interest in riding there spreads from a circle of hard-core mountain bikers to a wider community of recreational riders. To explore the depths of the majestic Copper Canyon, a bicycle may be the best way to experience a trip that feels like a journey back in time.

If You Go:

Most mountain bike trips are run in October, November, January, February and March. (The rainy season is July-August). The canyon area ranges in elevation from 1640 feet in Batopilas to 7875 feet in Creel. Weather and temperature conditions vary — it can be 20-25 degrees warmer on the canyon floor than on the rim.

Western Spirit

Starting and ending in El Paso, Texas, this is a back country trip with an emphasis on singletrack trails; (800) 845-2453, www.westernspirit.com.

Nichols Expeditions

The seven-day trip which includes hiking begins and ends in Chihuahua, Mexico; (800)648-8488, www.nicholsexpeditions.com.

REI Adventures

This nine-day trip, starting and ending in Los Mochis, Mexico, includes a first-class train ride, hiking and mountain biking; (800) 622-2236, www.REIadventures.com.

For general travel information in Copper Canyon, including train travel schedule and fares, visit www.coppercanyon-mexico.com.